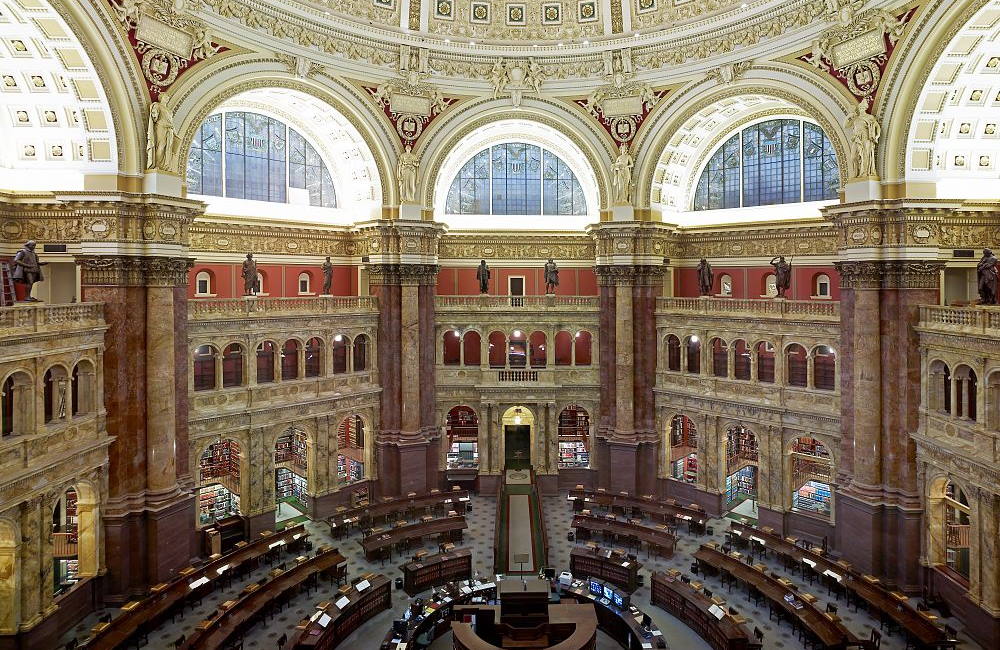

Library Of Congress Documents How Authorities Demonized Cannabis 100 Years Ago

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a movement began in the United States to make marijuana illegal with a campaign that focused on demonizing cannabis using racist stereotypes toward Mexican immigrants.

That’s the focus of new research by the Library of Congress that documents the beginning of the marijuana prohibition movement. It’s interesting reading, especially for those already aware of how President Richard Nixon launched the War on Drugs in the 1970s after some public officials spent decades demonizing cannabis.

Some of the material makes for tough reading. The library actually placed a disclaimer on its research that warned readers that many articles “contain ethnic slurs and offensive characterizations.”

They added that around this time “alarming reports of the menace of marihuana reached the United States press. Tales of alleged atrocities fueled by the drug are often tied to anti-Mexican propaganda.”

Propaganda War Against Marijuana Started More Than 100 Years Ago

For anyone seeking an example of how race and class divisions are used in propaganda, the LOC report on how the press covered marijuana a century ago provides an excellent case study. In some cases, coverage is infused with racism. In other cases, the reports show an aversion to facts and a habit of demonizing cannabis, often in strange ways (such as reporting on goats addicted to cannabis).

Whether this came from newspaper editors directing reporters or the public officials they covered – or both – is not known. The library provides a timeline of newspaper articles to show the pattern of cannabis demonization. Some highlights include the following.

New York Sun, Aug. 12, 1897. The newspaper offers a report from the Mexican Herald that states marijuana “continues to impel people of the lower orders to wild and desperate deeds.”

The Oasis in Arizona, July 15, 1899. The Arizona newspaper offers a harrowing tale (also from the Mexican Herald) ) on a “marihuana fiend” who allegedly broke into an office with a knife, declared he was Herod of Biblical fame and “his mission was the extermination of new-born infants.”

New York Tribune, April 11, 1909. This article claims a Mexican goat-herder has goats who have become addicted to cannabis.

El Paso Herald, June 3, 1915. When the El Paso City Council passed an ordinance to stop sale of marijuana, they labeled cannabis a “Mexican Drug.”

Ogden Standard, Sept. 25, 1915. This article has the headline of “Is the Mexican Nation ‘Locoed’ by a Peculiar Weed?” The article itself is even worse, suggesting cannabis is making bandits fight U.S. authorities and that marijuana-poisoned tea caused “the insanity of Queen Carlota.”

New York Sun, May 17, 1914. The headline says it all: “On Account of His Oriental Nature the Mexican’s Mind is a Puzzle to the Foreigner.” The article also claims that a man who smoked marijuana became delusional enough to think he could invade the United States by himself.

Meanwhile, In Texas, The Other Side of the Story (Sort Of)

The library included two articles that include positive information about marijuana, almost despite themselves.

One focused on James Love, who ran an experimental agriculture station in tiny Cuero, Texas. The Florida Star reported on Oct. 16, 1908, that Love had permission from the state to bring back 10 pounds of cannabis from Mexico to plant at his station.

“It is the belief of Mr. Love that the plant can be put to good commercial use as a drug,” the newspaper reported, proving Love a man ahead of his time. Love hoped cannabis might treat asthma and tuberculosis.

However, even in the midst of reporting something positive, the newspaper called marijuana “the most harmful of narcotic drugs” and wrote that its leaves “produce a series of insanity that frequently ends in death.” They also claim it caused riots among soldiers.

Another small item in the June 7, 1915, El Paso Herald focused on how “physicians and druggists” in El Paso felt the city council went too far in outlawing cannabis. They noted they prescribed it to patients because it is “a sedative of value.” As the library’s research shows, they were among the few to publicly voice this opinion in early 20th century America.